Lithic Breathing is a short experimental film that asks questions about our wild and resonating worlds—the world we inhabit now, and worlds that have come and gone. The project explores sea caves and pipe organs, and the ways that they can expand and entangle our thinking about ritual and breathing, listening and resonance, deep time and sense of place. Geophones, organs, viola, piano, stones, bells, electronic bows, transducers, field recordings and experimental lutherie come together in the making of a score that carves space for memory, imagination and encounter.

More About The Project

In the heart of Los Angeles, California breathes a pipe organ featuring over 4000 pipes.

Just south of the city breathe sea caves carved from ancient rock.

The caves have borne witness to our collective past, to the processes that shaped our planet and who we are. Ancient geological and oceanic forces birthed these rocks, and their configuration speaks to those forces. These rocks are keepers of climate memory.

Pipe organs too are relics of ancient worlds. Like sea caves, their breathing is a matter of apertures opening and closing.

This is a story about sea caves and pipe organs, and it is a story about the primeval interconnected forces that molded our world. It is a story that begins millions of years ago, with the emergence of these rock formations during the Miocene epoch roughly fifteen million years ago. This was an era of mastodons and megalodons, colossal sharks as long as school buses. This was the time of Livyatan melvillei, a prehistoric sperm whale whose namesake comes from the biblical sea monster Leviathan.

These rocks have borne witness to planetary change, loss and renewal, time and transmogrification, and they carry that memory in their chemical and physical configurations. Once upon a sea cave, these rocks saw a time when grizzly bears roamed California’s coastline, tunneling through the carcasses of beached whales. They saw a time of three-toed horses, ancient camels and toothy Smilodons. They have borne witness to the ghosts of planets past and to changing tides of evolution. And their very existence continues to shape natural history, by making possible a vibrant diversity of marine life.

Limpets graze their surfaces, often returning from their radula-scraping peregrinations to the same “home scar”. Tidepool sculpin (fish who also keep home territories) dart in the ever-warming, ever-acidified, microplastic-riddled shallows that pool. Anemones bloom on their submerged shelves. Crabs side-step their crevices. And these formations’ loose sandy sediments pulse with millions of meiofaunal organisms like hairy-bellied gastrotrichs, who navigate their world by specialized sensory hairs and slither by cilia through the sand grains like microscopic dragons.

Rocks shape life, and they are also shaped by life. Some rocks house endolithic microbes, and some of those microbes actually weather and even mine their home rocks. Sometimes the changes are faster and more perceptible: a veliger floats in on planktonic drift, tastes and smells the water for the presence of its kin, finds a soft rock where the others have made their home, and grows into a piddock clam. One side of its shell grows serrations, like a butter knife. As it grows, the clam twists the serrated side of its shell into the rock, drilling itself a burrow from which it can never again leave. The piddock clam spends the rest of its life in stone, filter feeding by means of delicate siphons, and leaves behind a burrowed echo of its existence.

Rocks are ancient storytellers. They have seen the coming and going of all the planets that have ebbed and flowed since then on this spinning rock we call Earth. Many worlds have blossomed and withered during their existence.

How can listening to rocks help us better understand—and reimagine—the stories of our oceans? Of our planet? Our entanglements with a larger geological story, with a rapidly changing climate? Our interdependence with geological processes, with a system of rock, water, air and more-than-humans?

What is it like to listen to the world through a fifteen-million-year-old filter of rock?

What does a sea cave’s memory sound like?

How might listening to the resonance of sea caves and to the low-frequency sounds of coastal geological formations connect us more deeply to our fragile coastal ecotones, to our planet’s storied past, to a new sense of scale and timefulness? Can experimental listening practices help us find new ways to think about rocks, deep time and our own sense of place? And how can new planetary perspectives catalyze new ways of relating to a sense of self?

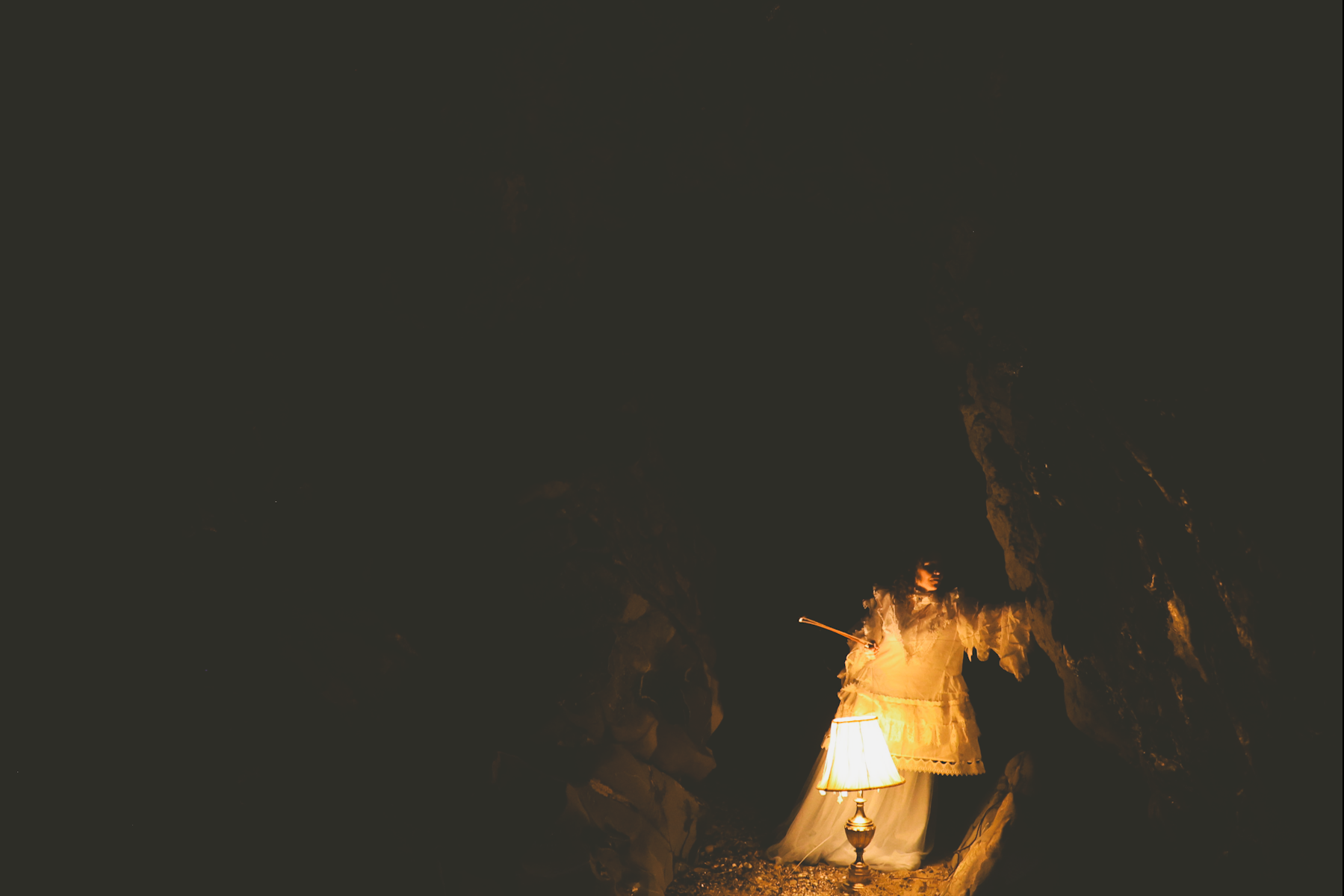

Geophones and experimental lutherie help us research these questions. When wire and bow transform a sea cave into a walk-in cello, our ears and minds open to the acoustics of more-than-human architectures and to the echoes of deep time. When we listen to a sea cave through a geophone—a sensor that detects low-frequency vibrations--we are listening to stone and we are listening through stone. We are listening to the sea through a filter of ancient matter. We are listening to the world through the remnants of past planets.

We are living in an era of climate anxiety and climate grief, and geological thinking through music is one way of meeting our present moment. What can we learn about our rapidly changing world—and our relationships with other living things, with ourselves--by finding new ways to listen? And how can listening help us imagine new futures in times of uncertainty? Geological thinking liberates our imaginations from the present moment, allowing us to speculate on what might have been, and what might be. Listening to and through rocks allows us to fever dream deep into our planet’s mercurial pasts and forward into its potential futurities. We can dream about not just listening to history, but shaping it.

Sea caves are ancient storytellers. They carry us back into deep time and forward into an uncertain future. They invite us to think geologically. What happens when we bring imagination, deep listening, and deep time into conversation? How can geological listening help liberate our imaginations from the present moment, allowing us to speculate on what might have been, and what might be? To dream about not just listening to history, but shaping it? To contemplate loss and transformation, weathering and metamorphosis, ancient landscapes and ancient soundscapes, living fossils and past planets, our place in time?

What can we learn from stories of the rocks that exist—as they have for millennia--beneath the places we gather? If rock memory is climate memory, what happens to our understandings of history, deep time, and sense of place when we stop to listen? If listening is an act of attention and care, how might lithic listening conjure new upwellings of planetary wonder, new imaginings of possible futures? What does rock memory sound like?

What happens when we start to open our ears and minds to cave voice, cave memory, cave time?

What stories do sea caves have to tell us?

…

Lithic Breathing features documentation of my work with prepared piano, prepared viola, prepared pipe organ, transducers, geophones, experimental lutherie, and live performances in sea caves and churches.

The score experiments with resonant space, vibrational architecture, string harmonics, dissonance, pipe organ polyphonies, and seismic rock recordings. Geophones and lithic lutherie open our ears to the resonant signatures of more-than-human architectures, and to the echoes of deep time.

The score features prepared pipe organ (activated with geophones and contact microphones), prepared viola (activated with sea cave stones, transducers, geophones and contact microphones), field recordings (sea caves activated with bow and wire; geophone recordings of sea caves and coastal environments), and prepared piano (plucked, keyed and activated with sea cave stones, welded key weights, transducers, seaweed, bells, viola bows, drum mallets, electronic bows, geophones and more).

Salvaged brass animals were welded into new amalgamations and used as key weights and sound sculptures.

For the field recordings, I recorded the sounds of sea caves being transformed into walk-in cellos via bow and wire. I also worked with geophones to record the sounds of sea cave rocks, and hydrophones to record the sounds of tidal hydraulics. Interwoven are field recordings featuring more-than-humans who build their lives around coastal geologies (roosting cormorants, feeding crabs) as well as more-than-humans from further afield who are nevertheless entangled in a web of global relationships.

Album Link

Credits and Gratitude

Bats recorded by Ben Kinsley at Campbient Residency, Manchester State Park, WA 2025.

Audio mastered by Michael Southard.

Organ music performed on the pipe organs at the Immanuel Presbyterian Church in Los Angeles.

Special thanks to Cabrillo Marine Aquarium, Bodega Marine Laboratory and Chapman University, where I recorded sounds made by hagfish, sea urchins, sea stars and more.

Thank you to the Experimental Music + Sound Art Fellowship and the Okada Sculpture & Ceramics Facility at Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts.

The outdoor sound sculpture installations were temporary and left no trace on the environment.